Case study site: Global

Primary forests are spatially diverse terrestrial ecosystems with unique characteristics, being naturally regenerative and heterogeneous, which supports the stability of their carbon storage through the accumulation of live and dead biomass. Yet, little is known about the interactions between biomass stocks, tree genus diversity and structure across a temperate montane primary forest.

Restoration of forest ecosystems by allowing continued growth of regenerating forests, active restoration measures, and re-connecting fragmented remnants across landscapes, will provide crucial mitigation benefits that contribute to emissions reduction targets as well as existing and future co-benefits.

Connectivity between conservation areas is vital for protecting and restoring biodiversity and ecosystems and can play a key role in supporting national responses to climate change, in Australia and around the world. Through a National Conservation Corridors Framework Australia could meet both climate and biodiversity outcomes and protect First Nations cultural heritage.

The need for integrated policy action to mitigate climate change and conserve biodiversity has now been recognised in Article 38 of the Glasgow Climate Pact. This emphasises the importance of protecting, conserving and restoring nature and ecosystems, including forests and other terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Our planet’s forests provide many benefits to society’s continued well-being yet are subjected to ongoing loss and degradation. These activities provide financial benefits but unless we understand the value of what is lost when the forests are cleared and degraded, we will not be able to make informed decisions about their use and management.

Data from Europe shows that there has been a major increase in the intensification of logging in Europe over the past five to seven years and this could prevent many European nations reaching their emissions reduction targets under the Paris and Glasgow agreements. The same process is now being pushed heavily by certain forest industry lobbyists and government agencies in several Australian states, including Tasmania, Victoria and New South Wales.

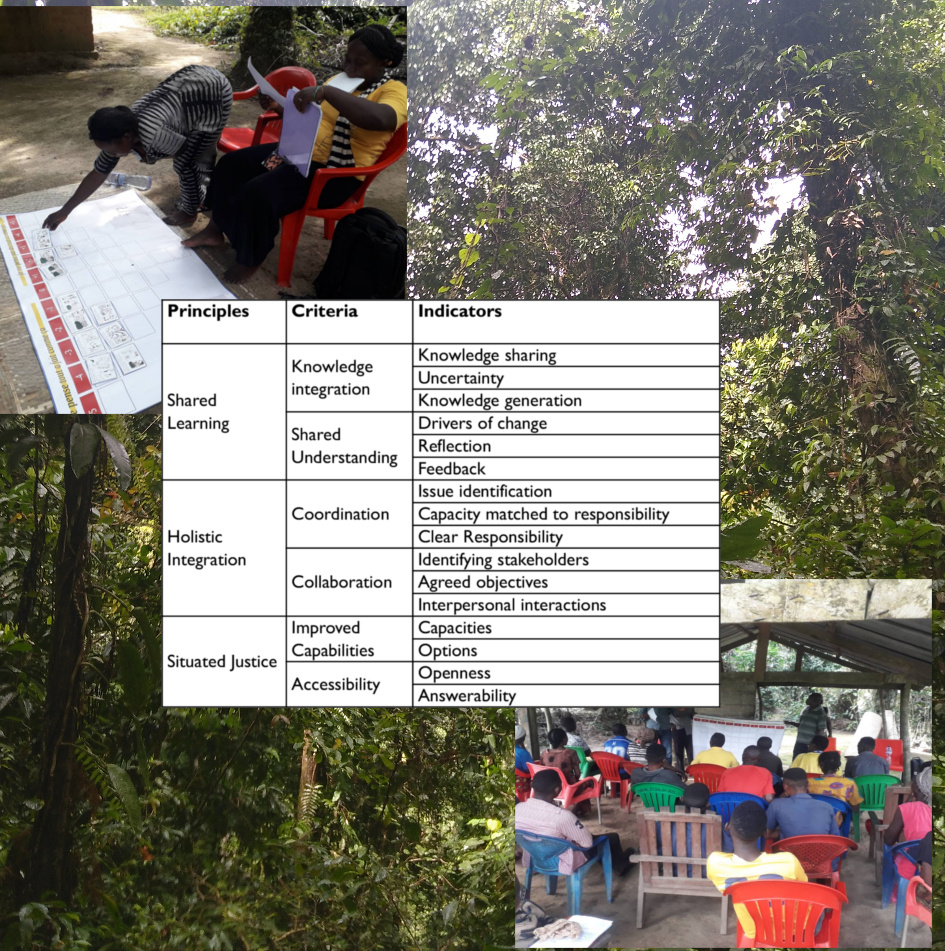

Effective planning is a key pillar of landscape management, but there are limited tools for evaluating planning, especially where planning is informal or nascent. This paper outlines a novel and robust principles, criteria and indicators framework for evaluating planning in contexts where there is limited formal planning.

The number of studies on valuation of forest ecosystem services is increasing over time, but limited in covering important regions and forest types. The values are diverse in nature for different forest features and ecological zones. The economic value is greatest when the ecosystem services are considered together, instead of when individual extractive uses are used in insolation.

Integrated landscape approaches to forest management are more holistic than conventional sector-based approaches and provide a more promising approach to sustainable management. Integrity-based Forest Management (INFORM) provides a framework for developing and evaluating integrated landscape approaches built on ecosystem integrity, effective planning and strong governance.

Integrated landscape management of forest landscapes requires ecosystem integrity, effective planning and strong governance. Integrated landscape approaches to forest management are more holistic than conventional sector-based approaches and provide a more promising approach to sustainable management.

The world’s contain irreplaceable biodiversity and are critical to the regulation of the global climate and maintaining stable carbon pools. Carbon-dense primary forests are found in every major forest biome and they typically support higher levels of biodiversity than logged forests, especially imperiled and endemic species, yet their value is not fully recognised in climate policy.

The climate change and biodiversity crises are intertwined. The loss of biodiversity reduces the resilience of both planet and people and narrows our response options for defeating climate change. Too often, though, biodiversity and climate change are dealt with in relative isolation by governments, intergovernmental processes, and other key actors and stakeholders.

The micro-economics teams from Griffith University and Woods Hole Climate Research Center introduce how environmental economics can play a role in demonstrating – or quantifying (often in dollar terms) many forest values – and economics can also play a role in designing schemes that can help forest communities begin to capture the benefits provided by conservation efforts.