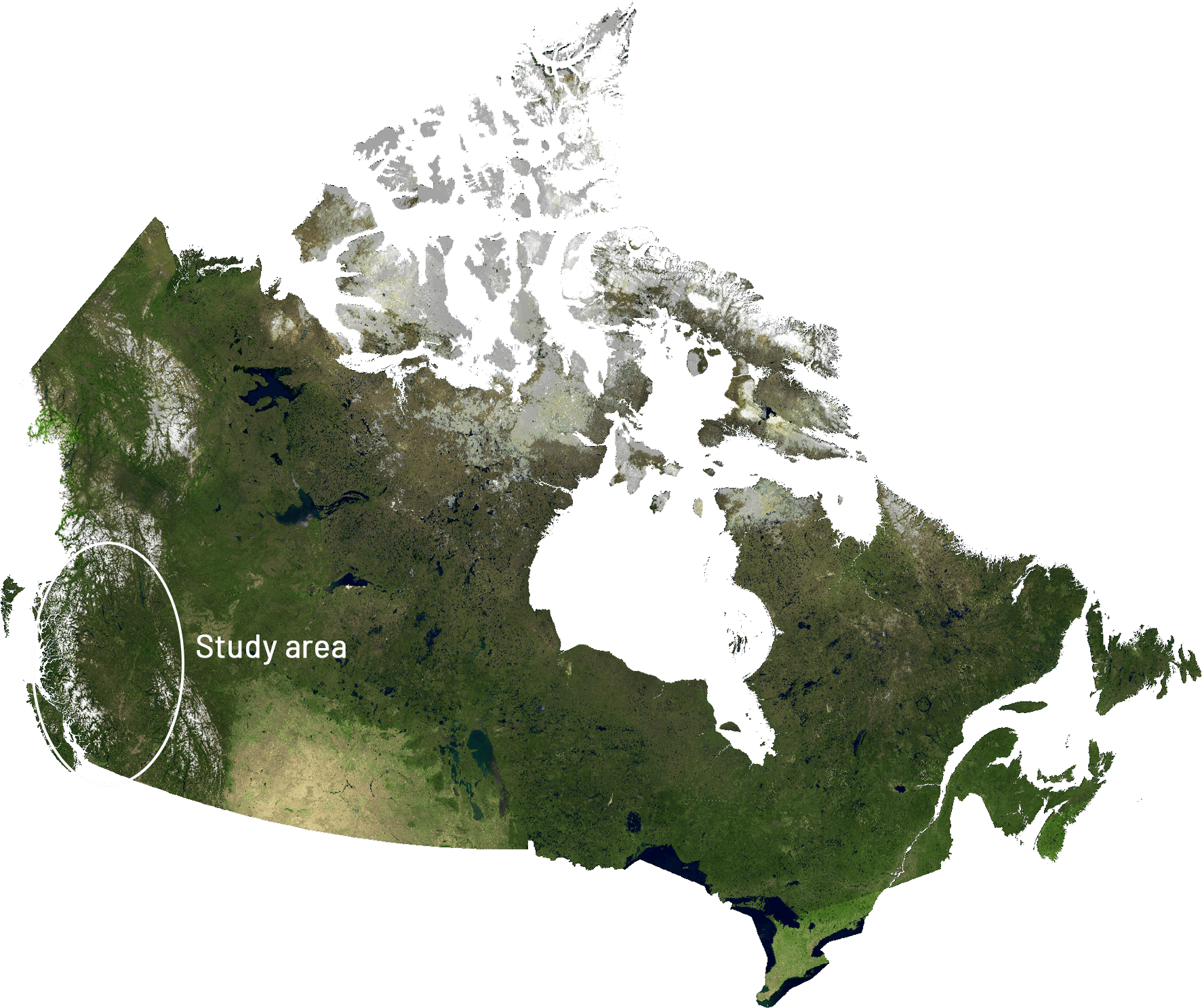

Inland Wetforest, British Columbia

British Columbia is home to significant areas of primary forest under threat from bioenergy

Located some 500 km from the British Columbia coastline, Canada’s 16.4 million ha Interior Wetbelt biome, which consists of several forest types, most notably inland temperate forests (~10% of the total area), is pressed against the western flanks of the Rocky Mountains and juxtaposed with the more distant Coastal Mountains to the west. Importantly, the inland temperate rainforest portion is globally distinctive as one of only three inland temperate-boreal rainforest regions worldwide (the others are in Southern Siberia and the Russian Far East).

Wild Heritage

Wild Heritage's mission is to protect and restore ecosystem integrity and safeguard biocultural diversity around the world and its focus in on primary forest protection, protected areas and ecological restoration. More about Wild Heritage.The Inland Wetbelt forest

The Wetbelt climate is exactly as the name would imply. While the entire area includes drier pine (to the east and south) and spruce-fir boreal rainforest (northern limits), it contains the wettest biogeoclimatic subzones within the interior cedar-hemlock forest. These forests are referred to as “forgotten rainforests”, so-called because, unlike their coastal counterparts which are largely protected by the “Great Bear Rainforest Agreement”, no such conservation agreement exists for the Wetbelt or its rainforest.

Why is the Wetbelt forest so important?

| Primary forest area | 1.6 million ha inland temperate rainforest |

| Carbon storage / sequestration | The upper bound on C densities is ~806 tonnes C ha-1, which is on par with some of the world’s most carbon-dense temperate forests |

| Keystone faunal species | Woodland caribou, numerous rare and endemic lichens, grizzly bear, wolf. |

| Supporting indigenous groups / local people | Enterprise benefits to local people. |

| Threats | Logging driven now by misleading bioenergy policies developed in Europe and Asia. |

Threats

Approximately 22% of the Wetbelt forests has been logged and/or developed since the 1930s, with logging concentrated in highly productive low-to-mid-elevation inland rainforest.

While the rate of logging has slowed somewhat since the peak in the 1980s, pressure is mounting to take ancient (>1,000 year-old) cedars from the inland temperate rainforest and 'bug-killed' spruce-fir boreal (higher elevations), which was previously deemed uneconomic, but which is now sold as 'feed stock' for bioenergy pellet manufacture and exported to Asia and Europe.

Despite evidence to the contrary, the pellets are being marketed as “clean, renewable energy” by Pacific Bioenergy near Prince George, BC, and by bioenergy facilities in Europe.

Forest carbon content (above and below ground biomass): Western North American Rainforests

| Forest cover (million ha) | Primary forest | Total forest carbon (tonnes) | Primary forest carbon (tonnes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Pacific Coast | 6.0 | 50% | 1.45 billion | 0.8 billion |

| Queen Charlotte | 0.98 | 45% | 0.24 billion | 0.12 billion |

| British Columbia mainland coast | 14.1 | 38% | 3.40 billion | 1.4 billion |

| Central Pacific Coast | 7.3 | 4% | 1.80 billion | 0.07 billion |

| North California Coast | 1.3 | 4% | 0.31 billion | 0.01 billion |

| British Columbia Inland Rainforest | 3.4 | 60% | 0.82 billion | 0.45 billion |

| Total | 33.1 | 34% | 8.0 billion | 2.9 billion |

Canadian Wet-belt landscape is being cleared of primary forests at an alarming rate.

Canadian Wet-belt primary forest is being wood-chipped and shipped all the way to Europe to be burned as what is currently called 'renewable energy'.

Solutions & responses

More robust conservation strategy

The Wetbelt needs a conservation strategy on par with the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement, which in 2016 increased forest protections from covering ~5% of reserves to 85% of reserves receiving some form of protection, and the remaining area under ecosystem-based management.

This protection should be managed in collaboration with First Nations from the current ~3% of all primary forests in protected areas, with the remainder in proforestation. Proforestation is forest management that allows degraded forests to return to their pre-logging carbon stores and can provide a critical role in drawdown of atmospheric carbon.

Such initiatives to protect new areas and develop proforestation can help Canada meet its biodiversity protection targets (17% of natural areas protected by 2020) and its obligations under the Paris Climate Agreement to cut emissions and protect carbon reservoirs.

Notably, the remaining rainforest provides an exceptionally stable carbon reservoir (very little fire) and is populated with the largest, oldest trees, and most diverse lichen assemblages. A greatly expanded reserve network would also provide an intact habitat for the region’s rare species – including many rare rainforest lichens and imperilled caribou – and compatible economic opportunities like carbon offsets for First Nations and timber companies. Carbon offsets offer the potential to retain logging concessions for protected area designations by levelling the economic playing field for conservation. Previously cut young forests may be able to meet regional timber needs.

British Columbia’s Wetbelt forests can play a vital role as a global carbon stock and sink in Canada’s efforts to meet climate mitigation objectives, including the Biennial Sessions of the FAO Committee on Forests (COFO24) and the United Nations Framework on Climate Change (COP24).

Notably, Article 5 of the Paris Climate Agreement encourages nations to conserve and enhance carbon sinks and reservoirs (stocks) of greenhouse gases, especially forests. To better meet its international obligations, British Columbia’s forestry practices need to be revised to accurately monitor and substantially reduce emissions from logging and other land uses. Remaining primary forests and natural areas could also be designated as World Heritage Sites, in collaboration with First Nations.