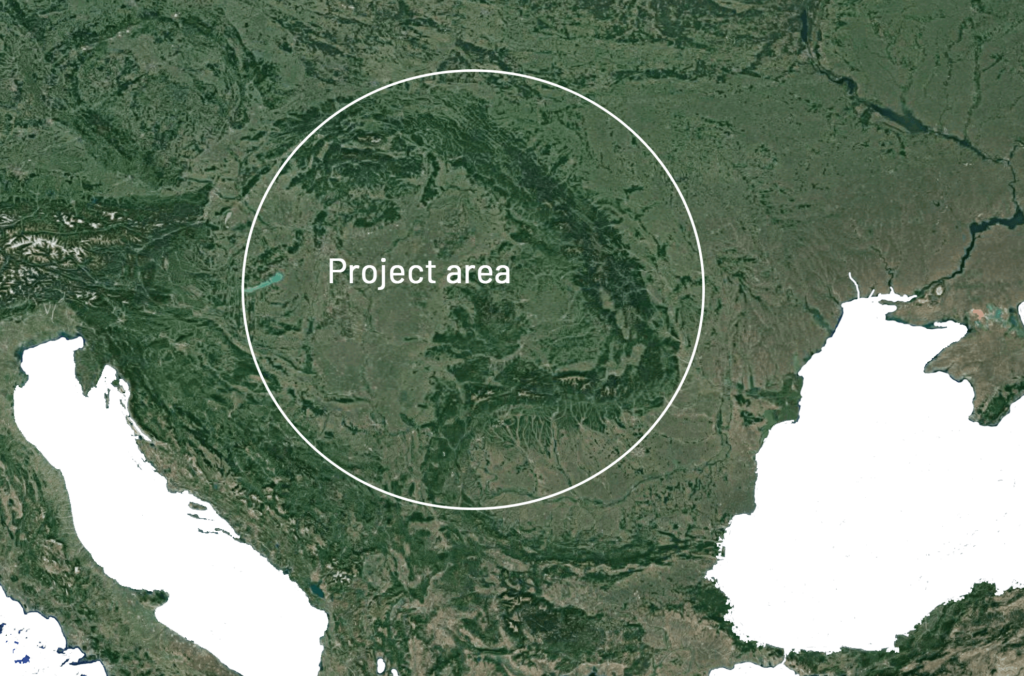

Carpathian Forests, Europe

The continent's largest remaining primary forests

The Carpathians hold Europe’s largest remaining tracts of primary and old-growth forests. They are a stronghold for brown bear, wolf, lynx, as well as lesser known endemic species and habitats.

Frankfurt Zoological Society

The Frankfurt Zoological Society is an international conservation organization. Its mission to conserve wildlife and its habitats in protected areas and areas of outstanding wilderness – by people, for people. It operates out in the natural areas themselves, supporting our partners in carrying out the practical conservation work.About the Carpathian forests

Forests cover of the Carpathian Mountains is over 10 million hectares (about the size of Iceland) across the Ukraine, Romania, Poland, and Slovakia. Whilst forests in Romania have been subject to massive illegal logging, forests in Ukraine remain largely intact and the potential for protection (and need thereof) is both high and urgent.

The use of wood-based bioenergy in the European Union, which increased 260% since 1990, pose the largest single threat to the Carpathian forests. With the current rules & public subsidies, 250% increase in demand is projected by 2027.

What's at stake

There are an estimated 330,000 ha of primary forest in the Carpathian region, in addition to much larger tracts of old-growth forests. The annual carbon sink potential of the overall Carpathian forests is estimated at 10 million tonnes with an estimated 1.7 billion tonnes of carbon stored in the Carpathian forests alone.

Romania has already lost 400,000 ha of its forests due to illegal logging. Forests in Slovakia and Poland are increasingly threatened by European Union biofuel demands. At least 1 million m3 of Ukrainian timber is already illegally exported to EU markets annually. Even so, Ukraine still holds the most intact forest tracts of the Carpathians.

Whilst the effects of climate change have decimated spruce plantations throughout the Carpathians, natural forest ecosystems have shown considerably higher resilience. Forest management must be adapted.

Forest carbon content (above and below ground biomass): Carpathian Forests

| Forest cover (million ha) | Primary forest | Total forest carbon (tonnes) | Primary forest carbon (tonnes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carpathian Forests | 11.2 | 3% | 1.73 billion | 66.5 million |

Current activity

Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and its national partners support 18 protected areas (PAs) across the Carpathians (total areas approx. 500,000 ha). Our focus is on improving the standards of protected area management, extensions and new designations, equipping park administrations (mainly rangers) to better carry out their tasks, and instituting world-class environmental monitoring systems.

FZS and its partners are leading on research projects to better understand the biodiversity and climate change mitigation value of the Carpathians. The focus of this research is always to inform better conservation.

On a European scale, FZS and the Wild Europe Initiative have begun undertaking advocacy work aimed at eliminating the logging pressure placed on the Carpathians by the EU’s biofuel policies.

Up-scaling protection

Large protected areas are the last bastions of large-scale and long-term forest protection. They should be expanded and provided with technical support (budget estimate all countries: $500,000 a year).

New designations will be supported (approx. 200,000 ha) in the region of all four target countries through data collection, mapping, ecosystem services research and targeted advocacy work ($150,000 a year).

Awareness raising, lobbying and advocacy work are desperately needed to combat the bioenergy challenge. The project will target a change of subsidy policy within the EU aimed at stopping the use of primary and old-growth forests as biofuels, both in Europe and globally ($150,000 a year).