Planning & governance

Building strong governance and effective planning for primary forest protection

Improved planning and governance are key pillars to protecting primary forests. Loss and degradation of primary forests is mainly due to human activities, such as industrial logging, mining and agriculture or increases in shifting subsistence agriculture. These choices of land uses and activities are determined by planning, while how decisions are made and activities carried out are determined by governance. Hence, sustainable management of forest landscapes requires both effective planning and strong governance.

Planning and governance are closely related - effective planning relies on strong governance, while effective planning determines the aims and goals of governance. The Primary Forests and Climate Project has developed and implemented novel, bottom up and collaborative approaches to evaluating and guiding planning and governance in primary forest landscapes.

Project members working on planning

Ed Morgan

Tim Cadman

Brendan Mackey

Strong governance

Governance is about how decisions are made and activities are carried out. To support primary forest protection, governance structures and processes need to be 'strong', in the sense that they effectively involve people in participatory structures and effective decision-making processes.

Strong governance is determined by:

- meaningful participation; and

- productive deliberation

1. Meaningful participation

Meaningful participation ensures that the multiple stakeholders in forest landscapes are genuinely involved in decision-making. Participation is essential to ensure the multiple stakeholders that depend upon and use the forest landscape are involved in decision-making. Meaningful participation relies on ensuring interest representation of the multiple stakeholders is inclusive, equal and resourced, and creating organisational responsibility to ensure accountability and transparency.

2. Productive deliberation

Productive deliberation ensures that decision-making processes are constructive and fair. Forest landscapes often have competing land uses, with multiple stakeholders seeking different goals. In this context it is important that processes are deliberative and not one-dimensional. It requires decision-making that is democratic, includes mechanisms for dispute resolution and results in agreement. It also needs implementation that seeks to address problems, creates behaviour change and is durable over the long-term.

This understanding of governance allows for the collaborative evaluation of existing governance, and can guide the creation of 'governance standards' by the stakeholders. These governance standards provide a basis for ongoing evaluation and improvement of governance of primary forest landscapes.

Effective planning

Planning is about deciding what land uses and activities are needed to meet needs and address future drivers of change. Planning is often associated with urban development, involving formal processes that result in formal plans. However, in many primary forest landscapes communities and other stakeholders are making decisions about future land uses and activities, and have done for centuries. These more 'informal' landscape planning processes are essential to maintaining the ecosystem integrity of the forest.

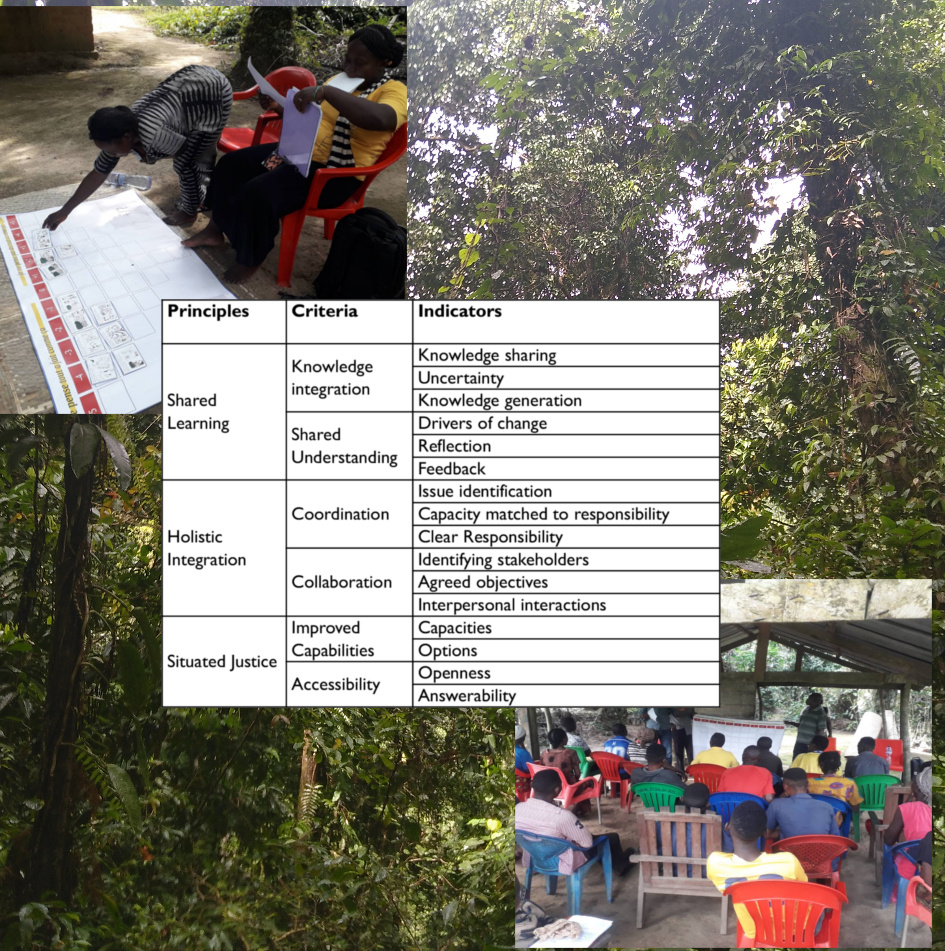

Effective landscape planning requires:

- shared learning;

- holistic integration; and

- situated justice

1. Shared learning

Shared learning recognises the multiple knowledges of stakeholders, including scientific, local, cultural and Indigenous knowledge, as well as the ongoing changes occurring in the landscape. Shared learning needs integrated knowledge of the forest and a shared understanding of the issues that affect forest landscapes and the people within them. Knowledge integration relies on sharing knowledge, acknowledging uncertainty and ongoing generation of knowledge. Building a shared understanding includes identifying drivers of change, as well as a process of reflection and ongoing feedback to ensure learning.

2. Holistic integration

Holistic integration recongises that landscapes are complex and can not be sustainably managed by focusing only on one sector or resource. Fully holistic integration is unlikely to be achieved but it is important to acknowledge the multiple and interacting land uses and activities occuring in landscapes. Integration requires coordination and collaboration of stakeholders.

Coordination is supported by identifying issues, assigning responsibility and matching resources to the responsibility. Collaboration is supported by identifying stakeholders, creating shared objectives and nurturing interpersonal interactions.

3. Situated justice

Situated justice recognises that there are power differences between stakeholders and these risk unjust distribution of benefits in uses of the landscapes. Although planning can be limited in addressing some of these power structures, it is important to acknowledge them their impacts. Situated justice rests on a capability approach to justice that seeks to improve capabilities, rather than seek perfect justice.

A capability approach seeks to identify and address capacity needs and create options for people, especially the most disadvantaged. Situated justice also requires accessibility to processes, which requires openness from all stakeholders to different views and answerability among stakeholders - a willingness to acknowledge and justify negative impacts on others.

As with governance, this understanding of planning provides the basis to evaluate planning, including informal and nascent planning, in primary forest landscapes. Evaluation helps ensure ongoing improvement of planning processes, including moves towards more formal planning where appropriate.

Evaluating planning and governance

One of the innovations of the Primary Forests and Climate has been focusing and and developing tools for evaluating and encouraging strong governance and effective planning. Just as evaluating canopy cover and forest loss is vital for understanding and addressing threats to primary forests, evaluating and understanding how decisions are made (governance) and what decisions focus on (planning) is key to improving the sustainable management of forest landscapes.